Some loads come with convenient holes in which to insert a hook to lift them. Most do not. It may be possible to rig slings around them, of fabric or rope or chain, but that is time-consuming, sometimes difficult, and possibly dangerous. But the great majority of loads come into one of not very many categories of shape, size and material, and for almost every load you can imagine there is some sort of specialised device to connect it easily and conveniently to a hook.

These, not unnaturally, are known as below-the-hook devices. There are many different types, and many different manufacturers of them, but in general they are of most use in a production environment, where repetitive lifting of similar or identical loads take place time after time. Weight is another factor: UK guidelines suggest that 25kg is the maximum safe limit for a fit male to lift, but if the requirement is for repeated and continual lifting the limit should be much lower. In practice on a production cycle, where loads are heavier than around 10kg, manual lifting should be replaced by some automated device, for efficiency as well as for safety – and it will obviously be much more efficient, as well as safer, if the device is designed for the load. We can go through such devices by the category of load that they are designed to lift.

Take, for example, the ubiquitous 210-litre (55-gallon US) steel drum. There are probably millions of them in workplaces across the world, and when filled – with oil, powder or liquid of almost any kind – they are too heavy for one man to lift easily. Nor do they have convenient lugs or holes or lifting points by which to attach them to a hoist and its hook. What they do have is a convenient rim around the top, which suitably shaped devices can grip. UK manufacturer Camlok, part of Columbus McKinnon, makes no fewer than three different designs that do exactly that (Yale, another Columbus McKinnon brand, makes one too).

First, in order of simplicity, is its DC500 Drum Clamp. It is basically an upside-down J-shaped lug that clips over the steel rim. A shackle connects it to a chain and your hook. A hinged tongue at the bottom locks the device into place when it bears the weight of the drum. One clamp is sufficient to lift an empty or sealed drum, which will hang from it in a tilted attitude. If your drum is open and full you will want it to hang level, in which case you will need two clamps per drum, fixed at opposite ends of its diameter and connected by a length of chain; your hook lifts the midpoint of the chain and all goes up safely, horizontally, and, we trust, without spilling. The working load limit is 500kg.

Camlok’s DCV500 vertical lift drum clamp attaches to just one point on the rim, but the lift point is at the end of an arm that reaches over the diameter of the drum at its central point, meaning that the centre of gravity of the drum is always directly below the lifting point, so the drum hangs vertically, whether it is full or empty. The DBT300 drum grab, under the Yale brand name, which is also part of Columbus McKinnon, is hand operated – pulling a lever moves arms that grasp the drum circumference and incorporates a tipping device. It is designed for the transportation, lifting, placing down, turning over and emptying of barrels.

Morse in the US are specialists not just in below-the hook devices but specifically in below-the-hook devices for lifting drums.

It has an 86-series, which supports the drum from underneath (with a side brace as well for stability); an 86-SS in stainless steel for harsh environments or caustic loads in the drum; an 86-S-2D for lifting two drums at once; and models with two lifting points, and with three lifting points, with added fork pockets. On its 86 series models the loads are manually secured. The Morse 90 series have remote grip and release; its 92 series will lift plastic or fibre drums as well as steel; the 41 series of lifting hooks are for carrying the drum horizontally rather than vertically; and we have not yet begun to exhaust its range. Morse is based in Syracuse, New York, and also has a European office in the Netherlands.

PALLET LIFTERS

Pallets are ubiquitous in material handling. They are, after all, the simplest, and the universal, way of moving heavy objects, collections of objects and stacks of objects – and the objects can be everything from bricks and concrete blocks to cardboard packages of plastic toys. Usually, of course, pallets are moved by forklift truck. But in many situations – such as manufacturing plants or packing plants – an overhead crane or hoist is to be preferred. Harrington Hoists, a Kito Crosby brand, has a range of pallet lifters that are attached below the hook.

Largest is the 20-ton capacity HPLHD – Fixed Fork Heavy Duty Pallet Lifter – which is counter-balanced so that it hangs level when unloaded. It is designed with a double frame to lift and carry heavy palletised loads efficiently with an overhead crane. The bail is a lower-headroom design, and is positioned to avoid side-loading the crane hook. Options with larger throat openings, and with greater outside fork widths, are available.

The 2.5-ton HPLAF comes with adjustable forks – the operator pushes them in or out to change their separation in order to handle various pallet sizes. The 1.5-ton HPLAH version has a hand wheel that does the same job. Both of these are counterbalanced. Its 3.0-ton capacity HPLLW – Lightweight Pallet Lifter instead comes with dual lift points as a method to allow the lifter to hang level when unloaded.

SCISSOR GRABS

The devices above are designed for lifting loads with particular shapes. There are also shapeless loads – that is to say, loads that are irregular, each one different, with no plane or smooth surfaces on them, and there are below-the-hook devices designed specifically for such irregular lumps.

Quarried stone, in the form of boulders, is the classic example – and the scissor grab is the classic lifting tool for them. Indeed, it has been so for some thousands of years: the Romans lifted their building blocks with scissor grabs – sometimes hand-held, sometimes attached to some kind of crane. Like the drum clamp, it is self-locking: it is the weight of the load itself that keeps the jaws clamped shut. It is a design has stood the test of time. Minicrane specialists GGR also make scissor grabs. Its Boulder & Stone Scissor Grab can be hand-held, in which case it is operated as a two-man device, or it can be used as a below-the-hook lifter on a hoist or crane in, say, stonemasons’ yards. It can lift up to 200kg. It has a 400mm capacity clamping range and is available with either rubberlined clamping faces or a metal tip to suit different finishes of stone.

You can go for a more high-tech solution from the same manufacturer should you wish. GGR’s GSK4600 Stone Lifter is a battery-driven vacuum-powered device. It is designed for lifting rough stone surfaces, concrete/stone stabs, or steel plate sections. It can carry out side lifts of up to 3,000kg and flat lifts of up to 4,600kg, making this a machine for lifting very sizable loads.

The onboard battery pack gives a 12- hour operating cycle, and an auto cut-off automatically switches off the pump when not in use to save energy. An audiovisual low vacuum warning notifies the operator if there is any loss of vacuum on the system, allowing the load to be lowered to the ground and secured as necessary.

SLABS

Staying with that boulder-moving stonemason, he may well be cutting his stone – marble, granite, limestone, you name it – into slabs, for selling as worktops, paving, grave markers, tabletops and the like. Again, there are specialist below-thehook devices for stone slabs. One such is the Kaiman Slab Lifting Clamp, from German makers Weha. This is a much more sophisticated machine than the scissor grab, though it works on a not dissimilar principle. It too is self-locking: this time the shackle lifting point to which your hoist is attached moves a rack-and-pinion arrangement inside the casing, which brings the two flat rubber-lined clamping jaws closer together, thus gripping the stone slab ever more tightly. It is for slabs of between 20mm to 60mm thick, and has a capacity of 1,500kg.

Yorkshire-based Stonegate Tooling is a company that like WeHa specialises in all aspects of stone fabrication, and so had developed its own below-the-hook lifter for stone slabs, but which is also suitable for ceramics, concrete, and indeed slabs of all kinds. Its Automatic Sky Rider Lifter has large pad dimensions of 490mm wide by 300mm high; the increased surface area is advantageous for lifting thinner materials, such as 4mm or 8mm porcelain. It, too, has rubber-lined faces to its jaws.

We mentioned scissor grabs (aka tongs) above, with reference to irregular shapes. Of course, a load does not have to be irregular in order to be lifted by tongs. Harrington makes a set specifically to lift long cylindrical loads – round bars, or cast or steel pipe of various diameters.

Its HBTA adjustable bar tongs can be used singly – in which case the load must be balanced, in other words supported at its midpoint – or in pairs, each one gripping the pipe at some distance either side of the midpoint. They have capacities from 0.5 tons, with 4in (100mm) maximum width, and, on the 1.0-ton versions and upwards, a hold-open latch. Replaceable urethane pads protect the pipe from damage.

ROLLS

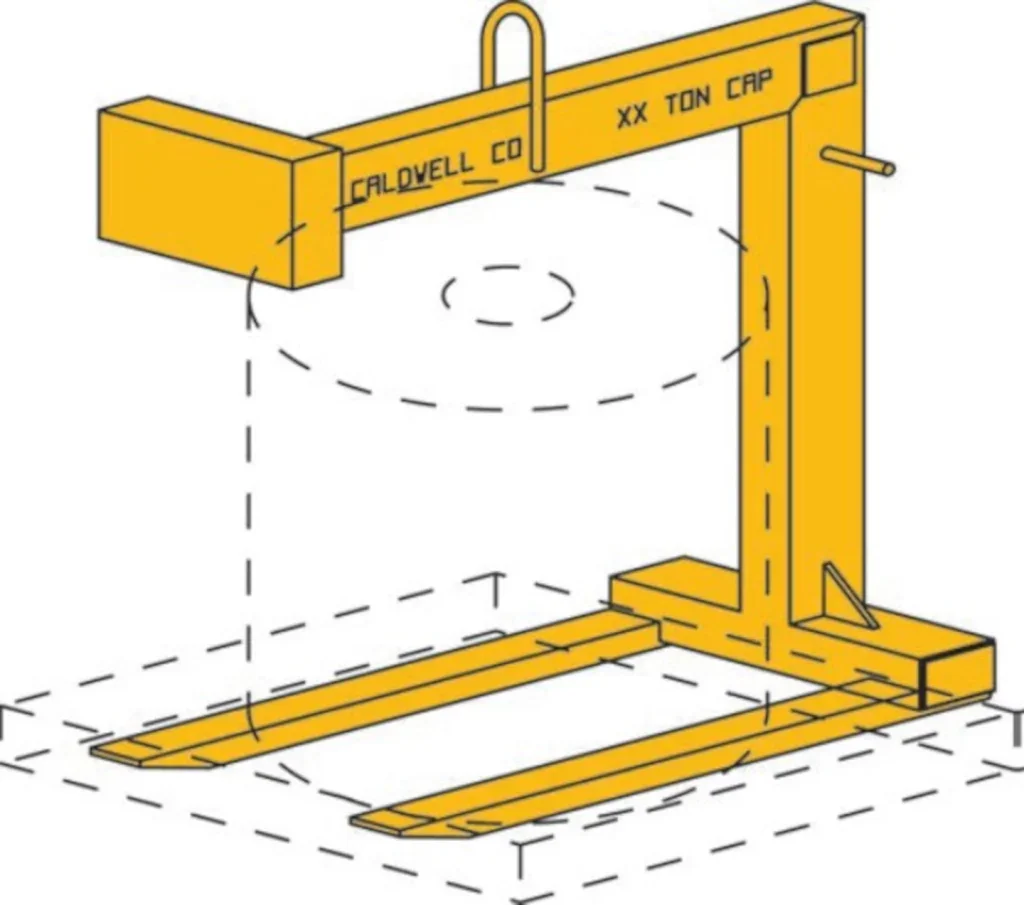

Rolls – of paper, of plastic film, of thin sheet steel, are another commonly lifted shape with its own specialised below-the-hook designs. Terminology can vary here. “With paper rolls, the centre is referred to as the ‘core’,” says Dan Brenneman, below-the-hook specialist at Caldwell. “But with steel coils or rolls and others, that space is typically just referred to as the ‘inside diameter’ or ID.

“Caldwell’s Model 90 lifts and transports the roll in an eye-vertical orientation, supporting it on its ends and leaving the core of the roll – the hole through its centre – open and pointing skywards. The Model 90P version carries them the other way, with the forks supporting the length of the coil and the axis horizontal. Both can lift up to 10 tons in their standard versions but we may be able to customise a unit to give a higher capacity if required.”

Short, stubby rolls – where the diameter is greater than the length – can be handled by pallet-type designs. Caldwell’s Model 90 lifts and transports the roll in a vertical orientation, supporting it on its ends and leaving the core of the roll – the hole through its centre – open and pointing skywards. The Model 90P version carries them the other way, with the axis horizontal. Both can lift up to 10 tons.

Longer rolls – visualise a carpet rolled up – may have a long hole through the centre, which is ideal to supply a lifting point; or they may have that hole already filled with a pole or rod that sticks out at either end – which again offers an attachment point. For the first of these, Harrington offers its HRLCH – Roll Lifting C-Hook, which is custom-made to specifications of length, capacity and so on. The long prong that forms the lower, carrying arm, part of the C fits securely into the inner diameter of the roll, holding it from one end only. The carrying arm should be as long as the roll, for safety and to support its full length. As with C-hooks for lifting shorter coils the design is simple, effective and efficient, and has no moving parts. Below-the-hook specialists Bushman offers its Model 600 C-hook, intended for paper rolls. A feature of Bushman C-hooks is that they can be equipped with integral load weighing systems. The accuracy of the load cells is from +/- 0.2% to 0.5% of full load.

Staying with long cylindrical rolls, for the second alternative of loads that come with a rod through the central hole and protruding at either end, the Mazzella Group offers a roll lifter in the form of a beam with hooks at each end; the rod fits into the hooks and is carried by them. Mazzella also offers an adjustable roll lifter in the form of a 2.0-ton capacity lifting beam that has shackles at each end to take the centre rod.

An alternative, requiring no kind of hole or rod at all, is simply to grasp the cylindrical load, whatever it might be, around the middle with a grab-like device. Camlok’s TRU Round stock grabs are exactly that: scissor grabs designed for round-stock material or pipes. Capacities are from 100kg to 4,000kg; with an optional protective lining it can pick up materials with sensitive surfaces – they should be dry, clean and free of oil and grease.

Almost every type of load will have some sort of device that is generally more efficient and almost always a lot safer than a simple hook, and for most loads there will be more than one choice of device and of manufacturer. Take your pick. There is a whole world of below-the-hook devices out there, and one of them will almost certainly be a good fit for your load.

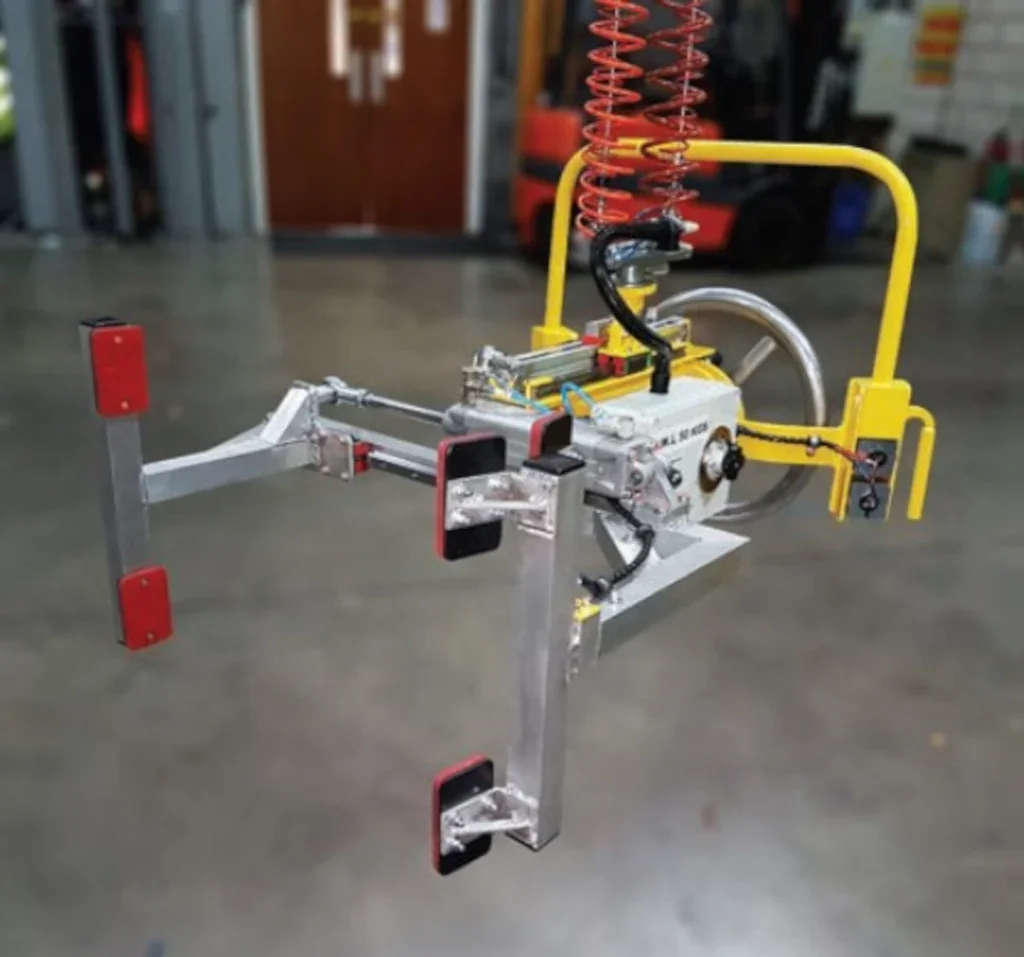

POWER-DRIVEN GRIPPERS HAVE IT WRAPPED

Power – electric, pneumatic or hydraulic – can transform the handling of heavier and some specialist or rapid-cycle loads. Handling Concepts of Stoke Prior in Worcestershire, for example, has a range of pneumatic grippers. Grippers, of course, hold up their load by friction – they squeeze onto the load from either side – and friction requires force, sometimes considerable force, which has to be maintained throughout the lift. Handling Concepts recently supplied a paper-processing plant with a pneumatic gripper that can lift loads of up to 50kg.

It grasps paper core tubes by pneumatic-powered arms, lifts them, and then rotates them through 90° so that they can be placed on a mandrel. The gripper itself is supported by a pneumatic rope balancer, which supplies the lifting power. The power for rotating the load however is manual, via a hand-wheel – but since the centre of mass is in line with the axis of rotation, this requires very little effort on the part of the operator.

The joint pneumatic and manual controls make a system that is intuitive to operate, and provide a solution that reduces risk of injury and increases productivity.