You can control a hoist or crane with a pendant with six buttons on it, hanging from a cable and dangling from the trolley of the overhead crane. Up, down, forward, back, left and right give all the axes of control that you might need while the operator can walk along, following the gantry, trolley, the hook and the load, pressing his buttons as he goes to get the load where it should be.

Or you can make it safer by removing the cable and replacing it with wireless controls. The operator can walk the factory floor as far from the crane as he likes, no longer limited by the length of a cable but pressing similar buttons on a hand unit such as Autec’s ‘LIFT’ series, which is roughly the size and shape of a TV remote. Autec have recently expanded their range to include two more models – the T10 and T12. The new additions feature more pushbuttons and available functions than their predecessors with 13 or 15 activations, respectively. Both models are available with either rechargeable or built-in batteries.

An alternative to the hand-held remote is the not-very-attractively-named ‘belly box’, which hangs on a strap around the neck – Magnetek, Danfoss, Scanreco and Hetronic are among many that offer this alternative. Or your operator can sit in a control room above the factory floor, pressing essentially the same buttons but looking down on it all, well out of harm’s way.

In earlier days, secure and interference-free connectivity was an issue with such systems; now, simple plug-ins are the rule, generally using the standard 2.4GHz or frequencyhopping technology. For instance, Street Crane Express offer their Street Sabre control system, with up to 12 pushbuttons on the hand-held controller and with frequencyhopping that allows up to 50 systems to run simultaneously without interfering with one another. Recharging time is 15 minutes for a full charge, while five minutes of charging time will give up to four hours of use. Also in this neck of the woods, Tele-radio introduced their nextgeneration wireless platform remote controller, the PAQ, in April at this year’s Bauma trade show.

This is not to say that the dangling cable pendant controller is obsolete. There are situations where wireless transmission is not allowed – working with flammable liquids, for example, or in explosive atmospheres, where there is a risk from sparking or static electricity. However, Autec, at that same Bauma show, featured an expanded range of their wireless transmitters for hazardous environments by introducing new Curve (AJQ EX), Link (AJN EX) and M-PRO (AJE EX) transmitters.

Or you can make the workplace more comfortable for the operator by removing the control room altogether from the site of operations. It can be placed far away, in another building (one less noisy and less dusty, an office building rather than a factory) or even in another town. No straight-line view of the operation is necessary: cameras, perhaps dozens of them, can cover the entire field of the crane’s operation and display the views more clearly and magnified as desired, on as many screens as are wanted.

And, for a process crane at least, whose movements are limited and repetitive in a known (and probably people-free) environment, even that scenario can be improved upon: the crane can be made autonomous. Sensors – vision sensors, proximity sensors, load sensors, velocity sensors, position sensors, the whole gamut – feed information to software, which then controls the crane. It is by no means necessary that the software be AI-driven; conventional programming can perfectly well suffice to pick up the loads, transfer them to the destination, and return to pick up the next load with no human intervention.

We can conclude that automation and control systems go hand in hand. How much automation one wants or needs; whether this degree of it will increase in the future and if so, can it be augmented with add-ons or will the system installed today need to be thrown out tomorrow; and how much a crane system needs to be integrated into the processes of the factory to make the entire plant a single sensor and data-driven entity with data feedbacks between the different components, all functioning together as an IoT (Internet of Things) system – these are all relevant questions.

An auto repair shop or a metal fabrication plant does not need such sophistication; a dangling cable control will do fine. On the other hand, a plywood production plant – where raw logs are fed in by a process crane at one end and plywood, palletised, stacked and wrapped in quantities and types ready-addressed to individual customers at the other – might well need this degree of sophistication and integrated control. In such plants, the logs are turned to make veneers; the veneers are rotated, pressed, glued, heated, cooled, sanded, knot-holes filled, sanded again; they are then passed by overhead cranes or a conveyor between half a hundred different complex and expensive machines; and a single large order arriving from a customer can be input into the system and selecting the quantity, feed rate and treatment can be determined and automatically controlled.

The auto shop and the plywood plant are at extreme ends of the spectrum. Most operations lie somewhere in between. But throughout the range, modular and upgradable control systems, such as future-proofing, are key concepts and manufacturers are embracing them. Examples of the latest generation of such integrated control systems are from Magnetek, part of Columbus McKinnon, which has its Intelli-guide system; and from Siemens, who offer its Simocrane system, which we shall come to later.

But there is a precondition to all the above. Whether your crane is controlled by cable, wireless or the most basic or the most sophisticated digital technology, the motors of your hoist must be responsive to their changing input. They must speed up, slow down or stop instantly on demand.

For accurate and efficient control of motors, for hoists and many other applications, Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) has become not merely desirable, but an essential component in modern automation systems. It allows a degree of precision and control of single-speed and 2-speed motors that was previously unavailable.

Variable frequency drives were introduced in the late 1980s with the advent of low-cost, high-speed power transistors. Initially, they were mainly used on the bridge and trolleys of high-speed Class D and Class E cranes. Today, they control every motorised motion on a crane from the hoist, the bridge, the trolley and sometimes even the rotation of the hook. “VFDs play a crucial role in modern automation and energy efficiency,” says Rhydian Welson, sales and marketing director of Invertek Drives. The company, of Welshpool in Powys, is a leader in the field and recently produced its three millionth VFD.

“In today’s competitive landscape, there is ever-increasing pressure to optimise processes, reduce energy consumption and minimise operational costs,” he says. “By providing precise control and energy efficiency, these drives help businesses achieve greater productivity, reduce their environmental impact and improve their bottom line. Latest advances in VFD technology can help businesses address the specific challenges they face in their industries.”

Advanced motor control algorithms, he says, are key to unlocking the full potential of automation and optimising performance and efficiency. It holds true for applications from simple pumps and fans to complex conveyor systems and industrial machinery, as well as for hoists.

Invertek recently launched its new Otipdrive VFD. It is, he says, the start of a new generation of VFDs entering the market. “By precisely controlling motor speed to match actual demand, Optidrive VFDs can reduce energy consumption by up to 40% compared to traditional motor control methods. This translates to lower operating costs, reduced carbon emissions and improved sustainability.”

Features such as sensorless vector control and high-speed communication options make it suitable for complex automation systems and applications requiring rapid acceleration and deceleration.

“Optidrive VFDs are designed with userfriendliness in mind,” says Welson. “The intuitive user interface simplifies setup and commissioning, reducing downtime and providing quick installation. This ease of use is complemented by a robust design that guarantees reliable operation even in harsh industrial environments, giving consistent performance and minimising maintenance.

“Comprehensive communication options enable seamless integration with a wide range of automation systems and protocols. This allows for effortless connectivity and data exchange, facilitating streamlined operations and improved overall system efficiency.”

The company is currently undergoing a major expansion, including a new 2,750m2 facility to increase production capacity to over 1.5 million drives annually. It has been estimated that some 80 million electric motors operate globally without VFD control; the investment underscores the growing demand for VFDs across various industries.

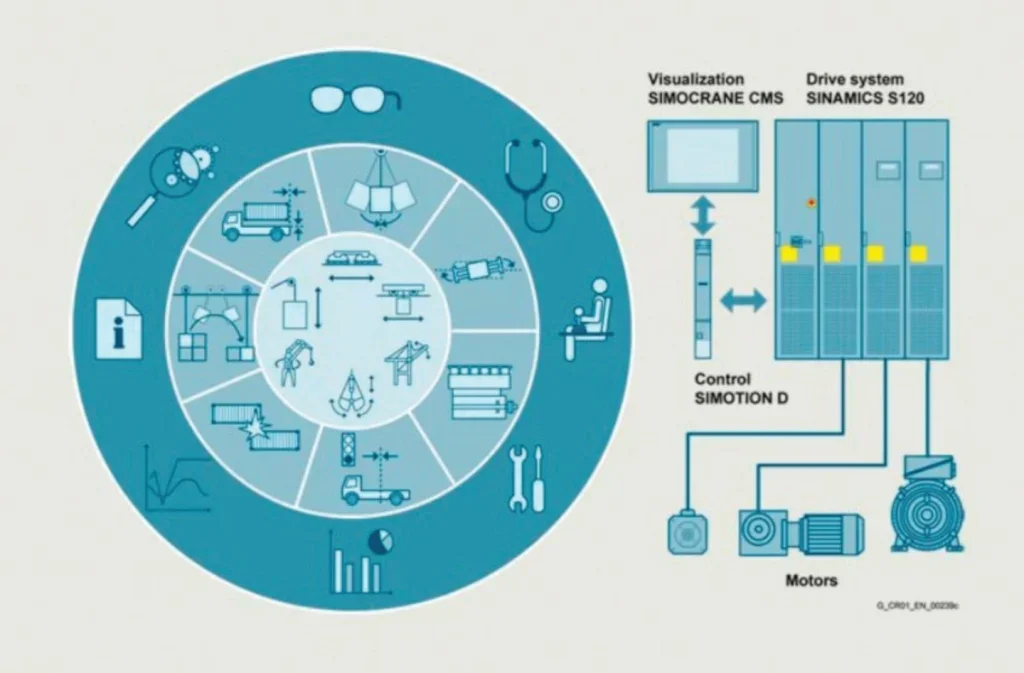

VFDs are central to the fully-fledged, automatically controlled crane and crane system. The software needs VFD hardware. In that arena of cranes controlled and integrated into their surrounding operations, Siemens offers its SIMOCRANE technology. It is modular and scalable. The ‘starter kit’, if I may put it that way, is the Basic Technology V5.0, a successor product to earlier versions with new software and better algorithms – it controls and optimises the motions of the different axes of the crane. It can be expanded with SIMOCRANE advanced technology modules, for example, Sway Control, Skew Control and Truck Positioning. This modular open architecture approach allows seamless integration of various hardware and software components to give flexibility and scalability. “By adopting an open architecture, operators can choose from a wide range of compatible devices and systems, simplifying the integration and ensuring adaptability for future upgrades,” says Siemens. It makes for a futureproof investment.

Siemens’ Remote Control Operating System takes it further. It relies on sensor and camera streams for applications – our earlier plywood plant might be one example – in which the cranes are integrated into the overall process, whereby the operator supervises multiple cranes, each of which works autonomously. Within the SIMOCRANE Technology Suite, an advanced Energy Management System using energy-efficient components and intelligent control algorithms minimises energy consumption and carbon footprints. Data on the usage, energy consumption, brake temperatures and wear and tear on trolley wheels gets sent back and forth, and is analysed by even more software to identify greater efficiencies. It has all come rather a long way from the man with the big control lever.

TELE RADIO LAUNCHES PAQ CONTROLLER

At Bauma in April this year, Tele Radio launched its next-generation wireless control product line PAQ, which it claims is “a step into the future”. The first releases in the range, the SupraPAQ TH76 and its associated new R30 receiver, are available immediately through the Tele Radio network; others will be coming l ater in the year. The PAQ line seeks to address the ever-changing needs of the industrial workplace with the most stringent safety requirements.

The new line comes with a dedicated smartphone companion app that is said to completely change the way users interact with Tele Radio remote controls.

The FieldManager enables operators to easily view device information such as online manuals and settings. The app can also be used to manage the settings and installed plug-ins of the device. For future releases of the app, more features will come to further simplify operations, allowing for wireless firmware updates, full data synchronisation, and remote support from Tele Radio technicians.

Security remains paramount in industrial remote-control systems, and the new platform can meet forthcoming safety regulations. The system maintains the critical emergency stop functionality but also introduces additional safety features that create multiple layers of protection for operators and equipment.

Each remote control’s functions – radio communications, plugins and security – are assigned their own processor unit. This creates a natural barrier between the different compartments and prevents mutual interference. Individual customer software can therefore never affect a remote control’s ‘vital organs’. RFID tags for permission management mean that only certified users operate the most dangerous parts of the machine.

The platform has been built in the C programming language. Users can, therefore, integrate custom plug-ins into the remote controls to tailor the system to their specific needs.

In future releases, the transmitters will be able to be run at the 433MHz and 915MHz frequency transmissions as well as the globally accepted 2.4GHz. There will be a rechargeable 2000mAh battery with a temperature sensor, and 48V charging for faster charging and extended runtime.

AUTEC POWERS POWER BAR

Besides the expanded range of transmitters for hazardous environments, Autec presented their Power Bar at Bauma this year – a modular and customisable belly box frame for transmitters that holds enlarged display screens that can be of 4.3in, 5in or 6.8in. Control buttons are configurable to the user and an ‘operatorpresence’ sensor, which is fitted to both sides of the frame, detects the presence of the operator’s hands. The idea is to provide an incentive for the operator to place his or her hands on the frame, improving operational safety. Sensor programming allows independent association between the left and right sides of the frame, which offers further customisation possibilities of commands and activation.

A ‘vibration feedback’ option alerts the operator to danger in noisy environments. The vibration is fully customisable in frequency and intensity. A ‘Night Mode’ option illuminates the control panel and adds a front torch beam. The Power Bar comes with Autec Studio, a proprietary programming tool designed to customise the graphical user interface of the display. Used by the AUTEC technical department, it can also be licensed to the customer for autonomous operations. The interface is intuitive and fluid, designed to minimise intervention time.

Autec controllers use Triband Technology, operating on 870–915MHz frequencies as well as in 2.4GHz bluetooth mode within a single system. This, says the company, is a major advantage that ensures global coverage of operational frequencies allowed for industrial remote controls and faster intervention in case of field interference.