Sling your hook

15 May 2018Slings are standard lifting kit and outwardly may seem to hardly change. But their safe use is always essential and developments may be in the offing, reports Julian Champkin.

The sling making and using industry is a conservative one, which may be no bad thing. Changes come slowly and with consideration. We asked various users and makers of slings their three recommendations for best practice. The answers came back: safety, safety, safety.

Nancy Ni, sales manager at H-Lift put it like this: “For overhead lifting, select the correct sling, and do not attempt to lift unless you understand how to use the sling, the mode factors to be applied, and so on.” Her second point was to inspect the sling before using it. “Do not use defective slings or accessories.” And the third was: “Never allow anyone to stand under the suspended load, or ride upon the load.”

Clear, sensible, and timeless advice. The major current change in the world of sling technology and practice, covered in last month’s issue, is the use of tagging— which among other things greatly assists in making easier the second of H-Lift’s recommendations above, that of not using defective slings or accessories. When we asked H-Lift about its most recent product improvements, that was the one they chose: “RFID tags are more and more widely applied to slings,” says Ni. “Embedded into metal or high-density synthetic carriers, RFID does not get crushed during normal service and allows customers to tag slings that are exposed to harsh environmental conditions—including extreme temperatures and exposure to oil, chemicals, water, dust and other contaminants.”

Safeway Sling, of Wisconsin, who make nylon, polyester, wire rope and chain slings, relate sling safety to frequency of inspection. Their three recommendations are to inspect according to sling usage— the more frequently a sling is used, the more often it requires inspection; to inspect also according to the use environment—the harsher the working conditions that the sling experiences, again the more often it requires inspection; and, thirdly, to consider sling service life—inspect older slings more often and base your conclusions on your previous experience in using the slings.

Their replacement guidelines are comprehensive. ANSI B30.9 gives criteria for removing slings from service. Among them are the presence of acid or caustic burns; melting or charring; holes, cuts or snags; broken or worn stitching in loadbearing splices; knots in any part of the sling; excessive pitting or corrosion in fittings; and signs of UV degradation.

To which Safeway Sling add their own recommendations: remove the sling from service if you see distortion in it; if it has an identification tag that is in any way unreadable; and any time that a sling is loaded beyond its rated capacity for any reason.

In addition, their slings have a red core safety yarn that becomes visible when the outer layers of the sling are worn—another indication that the sling should be retired. Safeway Sling hitherto has been notable as being one of the few women-only owned businesses in the industry. In April this year, however, they were acquired by Bishop Lifting of Houston. Bishop have their own recommendations for getting the best performance from webbing and round slings.

If lifting slings have been damaged, do not use them until they have been thoroughly examined by a competent person and declared fit for use. Improper or unbalanced loading, and overloading, should be avoided at all costs. And take note of the instructions and ensure that you are using the correct sling in the correct configuration for the job in hand.

Bishop also pointed out that most synthetic sling accidents are caused by sharp unnoticed objects cutting the material of the sling. In particular they identify the 90-degree edges of I-beams as particular points where the slings that go round them can be damaged. They offer their CornerMax wear pads as a solution. The pad holds the sling away from the corner of the load, preventing corner and sling from touching—in fact, the edge does not even touch the wear pad, they say. The pad is held in place by pressure against the two adjacent faces of the load but avoids the corner itself.

Anton van der Zalm, vice-president of corporate research and development at Van Beest, also raised the importance of bending radii. Bending a round sling made out of textile fibre through a tight radius at a hook or shackle weakens it, sometimes considerably.

Sharp edges are similarly to be avoided. IMCA lays out rules and guides for reduction in strength at different d/D ratios for heavier loads in marine environments, but for lighter loads and on-shore they do not apply.

“There are no standards or regulations for assessing these situations,” says van der Zalm. A rule of thumb is commonly used: the bend radius of the bearing surface of a sling should be greater than the thickness of the sling—in other words, a d/D ratio of one is borderline.

Finding this unsatisfactory, Van Beest, in combination with SpanSet and a technical committee of the DGUV, the German Social Accident Insurance, has tested the breaking strengths of various combinations of round slings and shackles—round slings, said van der Zalm, are generally used for heavier loads, flat slings for lighter.

The spectrum of capacities tested covered combinations of round slings and shackles, in the most common load increments from 0.5t up to 150t. They tested slings made of classic polyester fibres as well as those made from modern high-performance fibres. This, said van der Zalm, is of particular interest since the properties of high-performance fibre material differ from those of conventional polyester fibres.

It was found that the latter were susceptible to individual components separating from one another, and that damage occurred due to pressure at the contact points at the shackle radius; this was not observed in the modern fibres. The Van Beest website gives the full results of the tests. The company’s greenpin shackles are designed to address the problem by giving large d/D ratios.

“Technology is delivering stronger fibres,” said van der Zalm. “Much also depends on the weave.” Van Beest does not itself make slings, he adds: “Hi-tensile shackles are the core of our business, and slingmakers use our components.”

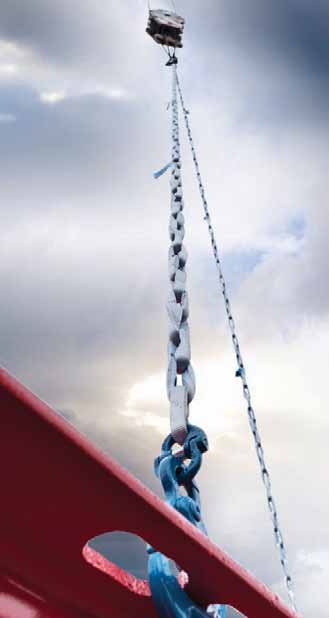

We mentioned above the acquisition of Safeway Sling by Bishop. Another acquisition may be an engine of change in the industry. In September last year, Van Beest bought Load Solutions, a Norwegian start-up company that was making synthetic chain—that is, chain each link of which is a webbing sling. “We bought it because they were a small company and needed finance to take the product to the next level,” says van der Zalm. The product is marketed as Green Pin Tycan.

The webbing is made from Dyneema UHMW (ultra-high molecular weight) polyethylene fibres, which the makers DSM claim is the world’s strongest fibre. Each link is formed of eight layers of webbing; one of the unique selling points is that the flat web is given a half-twist before the ends are joined to form a link.

Each link is therefore what mathematicians call a Möbius strip. The advantage is that the arrangement serves to equalise the strains in each of the eight layers of webbing. If the ends were joined conventionally, the innermost web-layer would be shorter than the outermost ones, and would carry either more or less of the load.

Whether you call the end result a chain or a sling is, frankly, up to you. It has qualities of both. It is claimed to be as strong as steel chain but eight times lighter. With a weight of 0.58kg/m for a 5t working load limit it is easily handled by one man. The links have inner length of 100mm and give 3% elongation at maximum securing load, 5% elongation at minimum break load. “It is completely different from anything that has been seen before,” says van der Zalm. “One advantage over conventional slings is that it is easy to shorten. Metal chains use shortening links to isolate a section of chain. The same method can be used on this system. Getting slings to the correct length is important when lifting with multiple slings, to ensure an even load distribution.

“We foresee a large market, for both on-shore and off-shore users, and for sub-sea as well; it has DNV GL certification for that already.”

The brand-new product is due to be launched to the public on 23rd April. “There have been some early adopters already,” says van der Zalm. “The market for slings does not change quickly. It will take time; but I believe this is a gamechanger”.