German Insight

15 November 2017The German overhead crane industry is vast and varied, with manufacturers of complete hoists alongside producers of consumables and components. Daniel Searle travelled through the west of the country to learn more.

Germany is famous for the scope of its industry, which ironically makes planning a week-long tour of the country’s overhead crane sector more difficult, as there is so much to potentially visit.

In the end, I aimed for a circular route starting at Stuttgart, travelling north through the regions of Baden-Württemberg and Hesse to North Rhine-Westphalia, to base myself in Düsseldorf, before returning south back to Stuttgart for my return flight, via Künzelsau en route.

As one might expect for a country with Germany’s reputation for industrial strength, the industry members I spoke to concurred on the current solidity of the domestic market. The consensus was that whilst the market may not be growing dramatically, there is steady growth from a very good initial position. And, due to the respected quality of German equipment, companies can rely on the export markets to bolster sales.

My first port of call was SWF Krantechnik in Mannheim, where I spoke with managing director Christian Heid.

“The German market is good,” says Heid. “It is still growing, although more slowly than expected. Therefore, we have higher export figures than anticipated—around 85–88% of our goods are exported.”

SWF Krantechnik sells almost globally, says Heid, although not in neighbouring France due to a sister company covering the region.

“We’ve seen strong sales to Belgium, Italy, Spain, Turkey, Australia, Indonesia, Vietnam, China, a couple of South American markets, and Russia has recovered well after sanctions were lifted.

In some export markets, such as China, customers request European equipment, to help guarantee safety on projects, which is becoming increasingly important in Asia.

“When one sector or country dips, others can grow—and because we serve a wide range of countries, this helps to keep our business steady. We did feel the effects of the dip in oil prices, but no so much. After the general drop of 2008–9, the fact that our business was spread out made it easier to recover.”

In Remscheid, around 30km east of Düsseldorf, I visited Kuli, and spoke with managing director Oliver Kempkes and export manager Oliver Riese. “Germany is still going well,” says Riese.

“It’s our largest single market. Europe overall has been steady for a few years but there has been little growth. We previously saw cycles of economy but currently the crane business is quite constant.”

That leads us again to the export market, which for Kuli is widespread and made more efficient by its network of partners and distributors.

“Our partners are usually crane manufacturers,” explains Kempkes. “They use Kuli components to complete their cranes, as girders can be manufactured in their domestic markets. The exceptions to this approach are in, for example, Africa, and on some islands.

“In the 1980s, my father shipped many completed cranes overseas—but we are now shipping fewer and fewer completed goods. We can provide specifications to our partners, and they are close to the end customers to give support.”

Riese adds: “This allows us to serve the markets much better. We don’t have a particular concentration of business in one region—we have good business in areas including America, the Middle East, Africa, and South East Asia.”

This gives balance to counter any market fluctuations, says Kempkes: “When sales of new cranes go down, refurbishments usually go up—then we can sell new wheel blocks, controls, hoists, and so forth. It’s a big advantage for us that we are widespread geographically and across various industry sectors—we cover the automotive industry, construction, chemical plants, assembly for machinery construction—and so if one area dips, we will be supported by another.

“It was interesting to see how the different markets reacted following the recession of 2008. By the time some markets declined, North America had already recovered.”

Heinrich de Fries GmbH, Hadef, is based in Düsseldorf, centrally located via a walk through the city.

“The German market has kept its high level stable for us for the last few years,” says managing director Eric Barbaras.

“It’s steady and established. Export sales are growing and there are new overseas markets recovering, like Russia or Iran, after sanctions are lifted.”

The company is also a supplier to the offshore sector.

“We have a subsidiary in Norway, with many years of experience in offshore projects,” says Barbaras.

“We have also increased our market share in winches by adding new models such as high capacity electric winches and ATEX models. Our complete products portfolio of hoists, winches and cranes is now also available in ATEX.”

In Künzelsau, east of Mannheim and arrived at via some quaint towns in the German countryside, I meet Thomas Kraus at Stahl CraneSystems, a dedicated manufacturer of ATEX cranes. The company is expecting strong growth in the next year, says Kraus.

“Because we manufacture ATEX cranes, we do a lot of work with the oil and gas sector, which is closely linked to the barrel price. After the dip in oil price, some investments were postponed—but we are expecting strong growth in 2018– 19, partly due to embargoes in markets such as Russia and Iran being lifted. “Business overall is steady, at a good level—and in Germany we are really on track. Our export markets are mixed— Asia, for example, is not doing as well currently.”

New Technology

As well as a reputation for quality, German manufacturers are also renowned for developing new technology—as they say themselves, the ‘vorsprung durch technik’ approach.

At Casar, based south-west of Frankfurt, near the French border, the company is pushing rope technology forward.

“Customers always want thinner and stronger ropes—partly because the size of the rope affects the size of the sheaves and drums,” says Pascal Ignor, mechanical engineer and product manager at Casar.

“We are pushing hard to produce hybrid ropes, which will have a synthetic core and a metal outer. It would be particularly beneficial to the mining sector, where ropes are lowered to depths of 3km or 4km. With 4km of metal rope, the weight of the rope is often almost at the maximum nominal breaking load before anything has been picked up. A hybrid rope would reduce weight by 10–15%, which would improve the payload per lift.”

The company is also looking into digitalisation and next-generation communication—known in Germany as Industry 4.0—and the potential, in the future, for ‘intelligent rope’ to improve understanding of what’s happening inside the rope.

As with any new technology, digitalised data gathering and transfer produces both opportunities, and problems to be solved.

“Every company is working on connecting devices,” says Heid at SWF Krantechnik. “It’s not the biggest challenge technically—but what is important is data security. Who has access to the data, and who owns it? It may be beneficial for partners to access data remotely for servicing and so forth, but some customers don’t want partners to have access—for example at power plants, which have to be very secure.

“Ultimately, the main goal is to make the end-to-end process as fast and economical as possible.”

Oliver Kempkes at Kuli says: “We are looking into integrated data and communications with other equipment.

At the moment, we are using status transmission, and data logging of lifts, which is the first stage of integration. The more data that is logged and shared, the more data security will be required—and more awareness of these issues from the industry.”

Collecting data is simple enough, adds Thomas Kraus at Stahl CraneSystems, which presents endless opportunities—so manufacturers need to focus on how best to use it.

“Everything can be fine-tuned—you can have ‘intelligent’ everything,” says Kraus. “It can be used for streamlining the production process, predictive maintenance, and various safety measures—such as by connecting equipment so they ‘talk’ to each other.”

SWF Krantechnik works through a network of partners to manufacture and sell overhead cranes across the globe.

The first stop on my tour of Germany was Mannheim, after travelling north on the train from Stuttgart airport. There I visited SWF Krantechnik, at the company’s training centre.

The company operates on a businessto- business basis, explains managing director Christian Heid. “We work through a network of distributors and crane manufacturers who build the cranes, rather than manufacturing the equipment here. Our partners oversee and manage the projects, although SWF Krantechnik has a technical team for bespoke systems, sales and aftersales.

“If an end user has a problem, our experienced and trained partners will handle it, but we will support them to see how it can be addressed.”

The company, which was taken over by Konecranes in 1997, has a network of around 500–600 partners worldwide, says Heid, and is expanding this partner network each year—some focusing only on servicing or distribution, and others providing full-scale crane manufacturing.

While the company is still expanding its network, it’s not all straightforward, says Heid: “We can foresee a challenge approaching, in that many entrepreneurs are now reaching an age where the next generation are having to take over.

However, the necessary exchange of industry knowledge and experience also presents the opportunity to combine the older way of doing things with modern approaches, such as using digital technology.”

The best way of passing information to partners is through training, says Heid. The company operates a training centre at Mannheim to train partners in service engineering, as well as completing commissioning and servicing themselves.

I visited the centre for a practical demonstration of its facilities, which focus around two hoists, that can be synchronised and operated in tandem.

“We have incorporated as many features as possible,” explains Heid. “And we keep the electronics panel at ground level so we can add ‘faults’ during training, such as wrong wires, for engineers to identify.”

There certainly are very many features to learn about. These include synchronised hoisting speeds for tandem operation of two hoists, both controlled from the same remote; the company’s Micro Speed technology which reduces the top lifting or trolley movement speed, for when accuracy is required; inching, through which a single button-press translates as a movement of a pre-set distance; floodlights that prevent glare and reduce power consumption; and a load display featured on the remote control.

The two Nova electric wire rope hoists at SWF’s training centre also feature the company’s shock load technology, which reduces the stress caused to the equipment by shocks, such as attempting to lift an oversized load. “Shocks can elongate the rope, which will eventually cause it to snap,” says Heid. “And they can also affect the integrity of the building. The technology reduces the speed to zero, and will automatically turn on in a potential overload situation.”

Another neat feature is load floating, which keeps the brake open for a short while after each move, to prevent repeated brake closures if the operator makes a series of short movements—thereby extending brake life.

Taking the controls, I was also invited to manoeuvre a multiple-tonne weight, to demonstrate SWF’s anti-sway system. The lifting height is detected, and the operator selects the sling length on the remote control, allowing the calculations to be made to produce optimum anti-sway.

Projects and Products

The anti-sway technology, which is made possible through the usual of inverters, also enables the speed to vary depending on the load—so, heavier loads will automatically go more slowly, and when the hoist has a lighter load or is unladen, the hoist will move more quickly. This saves time and power, says Heid.

The technology is being used at a steel fabrication facility in Switzerland, where SWF’s hoists were recently installed. Anti-sway was required, as the application involves handling long steel bars, which make for an unwieldy load.

With anti-sway, heavier loads can be handled safely and more accurately. Similar technology has also been installed at one of SWF’s partners’ training facilities in the Netherlands.

All of the company’s product lines are doing well, says Heid, and the company is serving lots of industry sectors. This is partly due to the range of products the company offers, says Heid: “As well as our standard range, we also offer the Fast Line series of pre-configured products, which are faster to make and ship, and the Blackline range of downsized systems, which are more simple, competitively priced, and structured for markets where the only requirement is lifting.

“We also offer a kit concept, where everything except the steelwork and the power supply are supplied.”

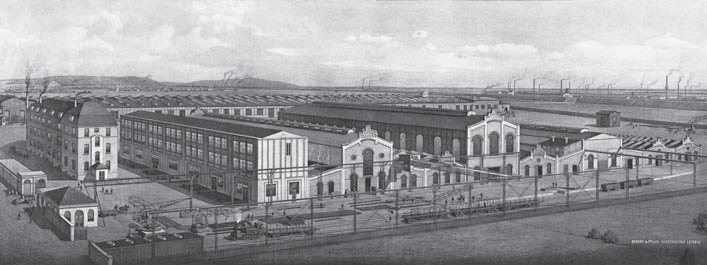

This is all manufactured through SWF’s network of partners; the company operated a production facility in nearby Heilbronn until 1997, when Konecranes purchased the company from MAN Group—which had acquired the company in 1973—and stopped production.

It does still stock spare parts though, including legacy spares for its discontinued equipment from the company’s history, which stretches back to 1921.

It’s a testament to the longevity of the equipment that orders of legacy spares can account for up to 30% of the company’s spare parts orders.

Part of WireCo WorldGroup, Casar is a manufacturer of wire ropes for use with hoists, cranes and mining

Visiting Casar’s facility in Kirkel, in the south-west of Germany towards France and Luxembourg, offers a fascinating tour through the process of manufacturing wire rope, and in particular the range of equipment used. The company combines some of the very latest, cutting-edge technology with machines that were built by the company according to their own design specifications and which are still running perfectly today—and Casar will celebrate its 70th birthday in the coming year. Pascal Ignor, mechanical engineer and product manager at Casar, talks me through the process.

“When coils of wire arrive, they need to be re-spooled, as the spools they are supplied on are not compatible with our rope manufacturing equipment,” says Ignor. “In 2016 we invested €2.2m in a high-speed spooling centre, featuring eight high-speed spooling machines. They have increased operational speed by 400–600%, even though before we were using 40 machines.”

The new spooling machines incorporate a laser measurement system to check the length of each wire during the spooling process, as well as automatic re-tensioning to maintain the correct tension.

Casar keeps a permanent stock of around 2,800t of wire, says Ignor, with various specifications and diameters, increasing in increments from 0.4mm to 4mm. The wire is typically supplied is three different tensile grades, and can be galvanised or ungalvanised. Special diameters, higher tensile grades and extraordinary wire coatings are also available but the company only buys such material for specific orders, so it is not part of the permanent stock.

All of the incoming material is tested—a small piece of each spool of wire is taken for testing, and the company won’t use any wire until the quality department gives the green light. The department uses a twin labelling system, enabling Casar to trace every single wire inside each rope, to assist with identifying any issues.

The testing department provides an interesting insight into the quality control process, with both manual and digital systems employed. The wires are tested according to the European standard EN 10264, but on a higher quality level. The diameter and the tensile strength are tested digitally and the data is transferred directly to a computer system. The tension and the torsion are tested manually. To measure the quantity of zinc on the rope surface, a chemical method called ‘gaseous volumetric method’ is used.

While those tests are conducted using table-top equipment, testing bending fatigue requires much more space. Casar keeps the rope running over multiple sheaves—over a distance of several metres—to test when both the point of discard and the rope breakage is reached. A typical test will run under 13.7% of the minimum breaking load, although that can be increased or decreased. Digital records are produced charting the length of time each process has continued for.

In the main rope production area of the factory, where the individual wires are connected to make the ropes used on cranes, further testing takes place. A breaking force test machine with capacity of 3,500kN tests the ropes—with the company planning to install a bigger machine, says Ignor.

If Casar designs its own end connections, EN 13411, the valid standard for all type of end connections, requires a so-called type test.

Through this, the rope is tested on an in-line testing machine with a determined cycling force along the rope axis for 75,000 cycles and then tested to see if it still achieves 80% of the nominal breaking load.

THE LATEST TECHNOLOGY

For mobile and tower cranes, rotation resistant ropes may be used—as the name suggests, they prevent accumulated twists in the rope making the load spin. To create rotation resistance, Casar designs ropes in a way that the helix of the outer strands goes in the opposite direction to the helix of the inner strands. Despite the advantage they provide, the company prefers to use conventional ropes where possible, as non-rotation resistant ropes are less prone to forcible twist and are able to handle fleet angles up to 4°.

For the completed products that will reach customers, Casar can provide very accurate lengths, if required, by measuring and cutting the rope by hand.

“This level of accuracy would be required for, for example, left and right hand ropes that will work together,” says Ignor. “For stock lengths, we use an automatic counter— although this does have small variances.”

One of the company’s latest products is the SuperPlast 10 Mix. It was launched in 2013, but the company is now receiving more and more feedback from its customers based on their experiences with using the product in their operations. The rope is designed to offer a very high bending fatigue performance and a high minimum breaking load, and as such is suitable for industrial cranes, and process cranes in paper mills and steel mills.

Looking ahead, the company has plans to produce thicker ropes, says Ignor. “We are aiming to produce ropes with a diameter greater than 90mm, which is our current limit. These would be used for sectors such as offshore.

“We may also install a machine for making ropes with very thin diameters—manufacturing these presents different challenges.

“We are looking at other innovations too, such as ‘intelligent rope’ which incorporates special load cells or even fibres to understand what’s going on inside the rope. But until now, this is still a long way off.

“Components such as rope grease also need to be considered. We are currently working with grease suppliers to improve environmental protection in the offshore sector.”

There are currently many tests in the field of VGP (vessel general permit) ongoing, adds Ignor.

Customers are always looking for thinner and stronger ropes, says Ignor—and in sectors where rope lengths are greatest, the weight of the rope is also an issue.

“We are looking into developing hybrid ropes, with a synthetic core and a metal outer,” says Ignor. “This would be particularly suited to the mining sector, where ropes can reach down as far as 3 or 4km. If you have 4km of metal rope, you are already almost at the maximum NBL.

“We are pushing hard to produce a hybrid rope, which would reduce the rope weight by 10–15%, thereby improving the payload of each lift. It’s a challenge for our R&D team because the elongation behaviour of steel and fibre is different—we have to find a way to unite them. There is also the issue with synthetics that to detect when it needs replacing, you can’t count fibre breakages as with metal ropes, so other methods are needed. More investigation into this is needed from the standards agencies and our team is supporting this strongly.”

Kuli manufactures every part of its hoists at its facility in Remscheid, using an unusual production set-up developed over many decades

Kuli, originally known as Helmut Kempkes after its founder, is based in Remscheid, not far by train from Düsseldorf. My journey takes me over the highest railway bridge in Germany, giving spectacular and vertiginous views over the forested valley below.

Kuli has a similarly vertical and interesting set-up at its facility—due to the shape of the premises it established in Remscheid in 1922, and due to the fact that the company produces all of its crane components from motors and gearboxes through to steelwork, the operations have grown into the shape of the building, rather than the other way around. Components are transferred across three floors, for each stage of the production process. It’s unconventional, but it works.

“One of our strengths is that our cranes are produced completely in-house,” says managing director Oliver Kempkes. “We don’t source components from outside the company. Therefore we are very flexible with customising designs; we can produce very simple or very complex equipment. “We are a mid-sized company with around 100 staff, which also helps to make us flexible—and we have a very high proportion of engineers, compared to other companies.

“Some of our customers buy large numbers of components to keep on stock, but we also have very specialised projects too. We need a mixture—we couldn’t do only special projects, but equally we don’t have the capacities to only produce standard cranes. It makes it interesting for our engineers as they work across many fields, and because our engineering and production operations are so close to each other they can test new approaches, such as with motors, the shapes of drums, steel construction, and so forth. This process becomes more complicated if you have to work with suppliers.”

Oliver Riese, export manager at Kuli, adds: “That’s particularly true if your suppliers are based abroad—producing components in-house saves time during product development and also when just manufacturing spare parts.”

The company tries to use standardised components, says Kempkes, but in different combinations, enabling them to produce specialised systems, and to manufacture parts more efficiently.

“Different voltages are used across the world,” says Kempkes. “So it is not possible to have all the combinations of different voltages with different hoists and motors in stock all the time. Instead, we keep the parts in stock and if a customer has an urgent demand for a specific part, we make it in-house.”

The company can also integrate other components if needed, though—for example adding a customer’s own control system, or making a motor with a larger shaft so the customer can add their own encoder.

It’s that flexibility that enables Kuli to complete specialised projects. An order from a steel manufacturer required an operator cabin that could withstand dust and high temperatures, as well as different controls to a standard crane; a 192t-capacity single-girder with a trolley on a curved beam was produced by combining standardised components with special arrangements; underground gantries for subway construction were supplied to Cologne, Düsseldorf and Hamburg; a crane at Dortmund railway station had to be built under the powerlines due to safety regulations but also had to withstand higher winds due to the trains passing by underneath; and a crane sold to an Antarctic research centre was particularly pleasing, says Kempkes, as it meant that Kuli had then served customers on all seven continents.

THE MANUFACTURING PROCESS

As one would expect from an operation that produces everything in-house—which also helps to keep costs down, notes Kempkes—there is an impressive variety of processes and components on show at the Remscheid facility.

The turning and milling machines use CNC technology to produce CAD-developed components and standardised parts. Motors are fitted with copper wire and sealed with resin to prevent it being affected by movements from vibrations— some cranes produced by Kuli in the 1970s are still running with their first motor, says Kempkes.

The motors are also built to a specific voltage, rather than a range of voltages, so that no safety margin is lost by operating a motor close to the edge of the range, and any power fluctuations can be accommodated.

Castings for motor housing are supplied to the company, but the machining is performed in-house. Elsewhere in the facility, much bigger pieces of metal are engineered into girders—and are moved from the welding station to the painting station using Kuli’s own overhead cranes, manufactured of course at the premises.

Any components supplied to Kuli are sourced as locally as possible, says Kempkes—the seamless tubes that are made into drums, for example, were invented in Remscheid and offer better and more consistent properties around the full 360°.

Overall, the hoists are designed to be maintenance-free, says Kempkes. They are robust, with three gears holding the load simultaneously; the planetary gearboxes provide a smooth transition; and they are suitable for low temperatures and sandy locations. The company manufactures with thick connecting rods and side flanges, which keeps the gearbox parallel and maintains the steadiness of the equipment in case of a crash, adds Riese—and each hoist is tested in-house under different conditions, such as at different voltages, with an overload, and more

Hadef has been operating for more than a century at its Düsseldorf factory, and the company’s goal is to maintain that stability and steady growth.

In the age of globalisation and demand for constant year-on-year growth, it’s refreshing to speak with a company that focuses on responsibility, both financially and to the local region.

Eric Barbaras joined Hadef’s Germany operations as operative manager after 13 years at the company’s French branch.

“We were founded in 1904,” says Barbaras, “So our strategy is for the long term. We have invested in our facilities to obtain a healthy increase of turnover. We want to grow consistently and steadily.” Hadef is family-owned, with no external investors. The Düsseldorf facility was expanded by 2,500sq m a few years ago, to increase capacity for future growth, says Barbaras.

“The market has changed over the last few years. There has been consolidation and concentration, due to limited growth in the market. The German market has been stable for about three years—it is at a good level for further growth.

“Our main target is to continue to manufacture our products in Germany and Europe. This ensures the quality stays high. We are proud of being a manufacturer in Germany, and we are proud of our well trained employees and their dedication to the job.”

The team of 150 employees provide Hadef with a great deal of know-how, says Barbaras, and in return they have an interesting scope of work: “To work for Hadef, you need experience and knowledge, because there is a wide range of different tasks every day.”

Building the Hoists

Following the facility expansion, Hadef is constantly investing. The latest technology laser cutting has recently been installed in the factory.

“We are always looking to innovate, relying on our experience and heritage,” explains Barbaras. “We are constantly pushing progression and evolution in our communications and production.”

The company has increased its market share in winches, especially in high capacity winches and they have added ATEX models to their portfolio.

It produces manual, pneumatic and electric chain hoists, cranes and winches, with the whole range also available in ATEX, says Barbaras—the company’s strength is the wide range of products it offers, and the number of possible applications and sectors it can therefore serve.

Most of the components Hadef requires, the company produces in-house. Walking round the company’s production floor, the variety of machining processes is clear to see. The products are tested before dispatch on different test facilities including a natural weights test rig for up to 125t capacity.

Robots are used to manufacture parts and for welding, to ensure the highest level of quality. There is also attention to detail, such as a roller shot blasting machine used to blast parts prior to painting, which allows the paint to better adhere to the equipment—which is particularly demanded by the offshore sector where conditions of the environment are tough. To dry the paintwork, components are suspended in a separate area that is kept at a steady temperature, at the optimum for curing the paint

Stahl CraneSystems specialises in ATEX lifting equipment, with a focus on growth and new products under the company’s new owners.

Travelling down from Düsseldorf to Stuttgart airport to complete my tour of Germany, I took a detour to Künzelsau, through some picturesque countryside and small villages. There I visited Stahl CraneSystems and met Thomas Kraus, head of the company’s Support Center.

Business is steady, but at a good level, says Kraus—and is particularly on track in the company’s domestic market. Due to the company’s focus on ATEX products it therefore works closely with the oil and gas sector, which is strongly linked to the barrel price; when that fell there was a period where investments were postponed, but after various embargoes in national markets were lifted the company is anticipating strong growth in the sector in 2018 and 2019.

“We’re one of the leaders in ATEX lifting equipment,” says Kraus. “We have very strong engineering capabilities here, and produce high-quality products.

“Reliability is the key in the oil and gas sector. Time lost is money lost, so equipment need to be fully tested and working before it’s supplied. We have a facility in Dubai where we can perform test lifts up to 250t, and perform all the necessary tests to ensure it’s in full working order, before the cranes are shipped to customers in the region.

“In the LNG sector we manufacture hoists for applications such as lifting pumps out of tanks—we supply all the major EPC contractors. The ATEX sector is very specialised due to the level of care and detail required. We are supplying a big refinery in Russia at the moment, for example, and it is particularly demanding because of the amount of special documentation required.

The sector is specialised due to the level of safety required, the cost of downtime to the end users, the long lead times involved and the long bidding phase, the varied individual needs of each customer, and then the number of on-site tests required and the inspections made at the facility.”

Despite the specialised nature of the finished products, everything is based on Stahl CraneSystems’ standard products, with the modular design enabling the company to make modifications from there.

Columbus McKinnon took over the company earlier this year, after former owners Konecranes were required to divest the business after their acquisition of Terex’s Demag MHPS business. The main goal now, says Kraus, is to grow the business and develop new products.

As well as producing ATEX equipment, the company also produces standard hoists, and has a number of ongoing projects to develop new and existing products. The company is currently refurbishing its ST series of chain hoists, and is also adding smart features one by one, to improve elements such as data logging, communication, preventative maintenance, and so forth.

A Streamlined Set-Up

All of the engineering is done at Künzelsau, but with 650 employees at the company and nowhere for the 20,000sq m facility to expand into—the site has expanded but is now hemmed in by a river and the roads—the company has developed a very organised, streamlined set-up to optimise the use of the space.

“Our biggest challenge is space,” says Kraus. “But it forces you to be organised and to think of creative solutions.”

The various components—all of which are made in house, due to the requirements of ATEX projects—are manufactured in the most efficient order; for example, gears, motor housings and motors are all produced in one area, so they can be assembled in one place. The gears and gearboxes are producing using fully-automated CNC technology, which halves the price of manufacture and helps to keep Stahl CraneSystems competitive, says Kraus—the streamlined set-up also enables the company to produce higher volumes while keeping costs low.

The company uses a combination of automated and manual welding—they have good engineers, explains Kraus, so it makes sense to use their skills. Powder coating is used rather than conventional paintwork, as it gives better coverage, particularly inside tubes.

Once produced, the finished cranes are stored at a facility nearby, rather than at Künzelsau, again to make best use of the space The machining system installed at Stahl Crane Systems incorporates an automated stocking system, and can run 24 hours a day.

The machining system installed at Stahl Crane Systems incorporates an automated stocking system, and can run 24 hours a day.

Casar increased its wire spooling capacity by several times by replacing 40 old spooling machines with eight new units.

Casar increased its wire spooling capacity by several times by replacing 40 old spooling machines with eight new units.

Thomas Kraus with a hoist that features one drum, two motors, and two gearboxes, adding redundancy safety for industries such as the metal process sector.

Thomas Kraus with a hoist that features one drum, two motors, and two gearboxes, adding redundancy safety for industries such as the metal process sector.